Understanding React Hooks

React Hooks are a way for your function components to “hook” into React’s lifecycle and state. They were introduced in React 16.8.0. Previously, only Class based components were able to use React’s lifecycle and state. Aside from enabling Function components to do this, Hooks make it incredibly easy to reuse stateful logic between components.

If you are moving to Hooks for the first time, the change can be a little jarring. This chapter is here to help you understand how they work and how to think about them. We want to help you transition from the mental model of Class components to function components with React Hooks. Here is what we’ll be covering:

- A quick refresher on the lifecycle of Class components

- An overview of the lifecycle of Function components with Hooks

- A good mental model to understand React Hooks in Function components

- A subtle difference between Class and Function components

Note that, this chapter does not cover specific React Hooks in detail, the React Docs are a great place for that.

Let’s get started.

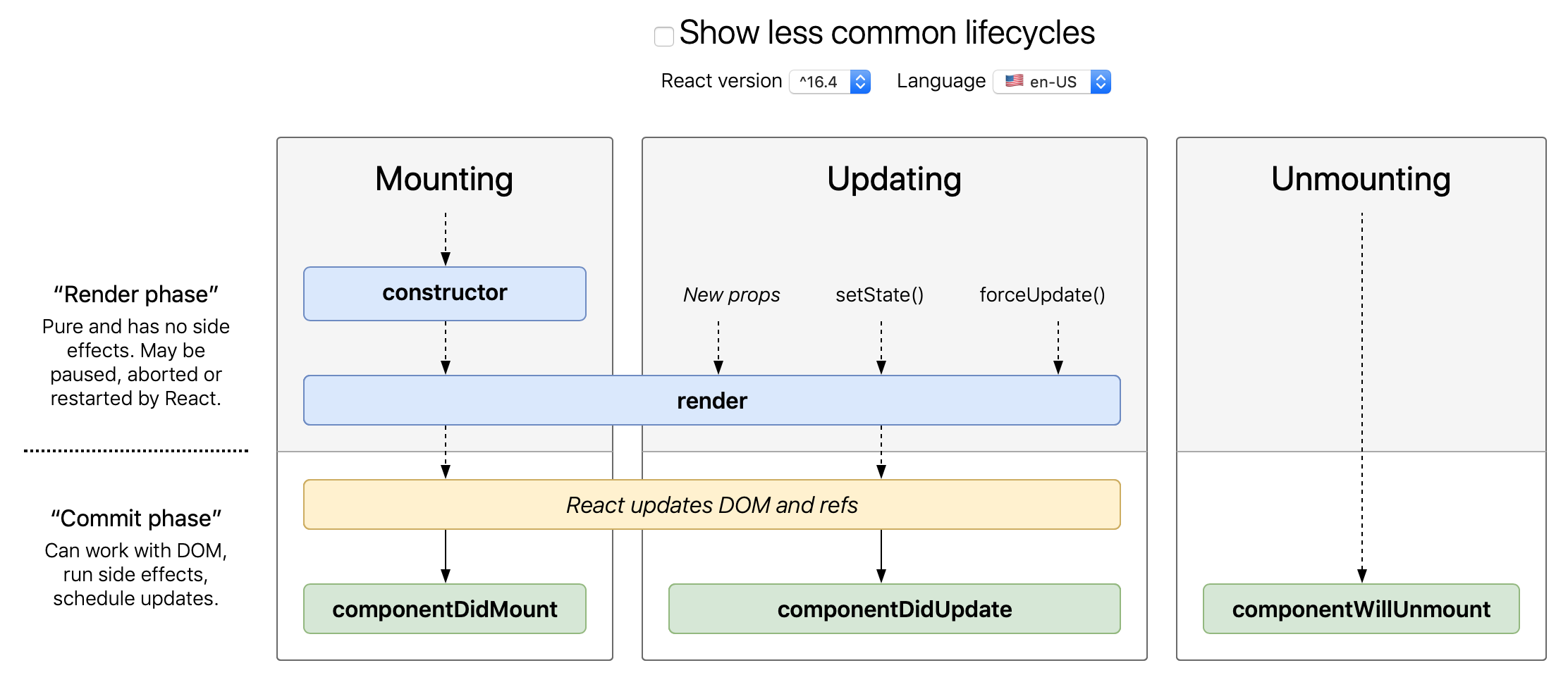

The React Class Component Lifecycle

If you are used to using React Class components, you’ll be familiar with some of the main lifecycle methods.

constructorrendercomponentDidMountcomponentDidUpdate`componentWillUnmount- etc.

You can view the above in detail here.

Let’s understand this quickly with an example. Say you have a component called Hello:

class Hello extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

}

componentDidMount() {

}

componentDidUpdate() {

}

componentWillUnmount() {

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Hello, world!</h1>

</div>

);

}

}

This is roughly what React does when creating the Hello component. Note that, this is a simplified model and it isn’t exactly what happens behind the scenes.

- React will create a new instance of your component.

const HelloInstance = new Hello(someProps); -

This calls your component’s

constructor(someProps). -

It’ll then call

HelloInstance.render(), to render it for the first time. -

Next it’ll call

HelloInstance.componentDidMount(). Here you can run any API calls and callsetStateto update your component. -

Calling

setStatewill in turn cause React to callHelloInstance.render(). This is also the case if React wants to re-render the component (maybe because its parent is being re-rendered). -

After the updated render, React will call

HelloInstance.componentDidUpdate(). - Finally, when it’s time to remove your component (maybe the user navigates to a different screen), React will call

HelloInstance.componentWillUnmount().

The key thing to understand about the lifecycle is that your Class component is instantiated ONCE and the various lifecycle methods are then called on the SAME instance. This means that you can save some sort of “state” locally in your class instance using class variables. This has some interesting implications that we’ll talk about below.

But for now, let’s look at the flow for a Function component.

The React Function Component Lifecycle

Let’s start with a basic React Function component and look at how React renders it.

function Hello(props) {

return (

<div>

<h1>Hello, world!</h1>

</div>

);

}

React will render this by simply running the function!

Hello(someProps);

And if it needs to be re-rendered, React will run your function again!

Again we are using a simplified React model but the concept is straightforward. For a Function component, React simply runs your function every time it needs to render or re-render it.

You’ll notice that our simple Function component has no control over itself. Also, we can’t really do anything with regards to the React render lifecycle like our Class component above.

This is where Hooks come in!

Adding React Hooks

React Hooks allows Function components to “hook” into the React state and lifecycle. Let’s look at an example.

function Hello(props) {

const [ stateVariable, setStateVariable ] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

console.log('mount and update');

return () => {

console.log('cleanup');

};

});

return (

<div>

<h1>Hello, world!</h1>

</div>

);

}

We are using two Hooks here; useState and useEffect. One tells React to store some state for us. While the other tells React to call us during the render lifecycle.

-

When our component gets rendered, we tell React that we want to store something in the state by calling

useState(<VARIABLE>). React gives us back[ stateVariable, setStateVariable], wherestateVariableis the current value of this variable in the state. AndsetStateVariableis a function that we can call to set the new value of this variable. You can read about how useState works here. -

Next we the

useEffectHook. We pass in a function that we want React to run every time our component gets rendered or updated. This function can also return a function that’ll get called when our component needs to cleanup the old render. So if React renders our component, and we callsetStateVariableat some point, React will need to re-render it. Here is roughly what happens:// React renders the component Hello(someProps); // Console shows: mount and update ... // React re-renders the component // Console shows: cleanup Hello(someProps); // Console shows: mount and update -

And finally when your component is unmounted or removed, React will call your cleanup function once again.

You’ll notice that the lifecycle flow here is not exactly the same as before. And that the useEffect Hook is run (and cleans up) on every render. This is by design. The main change you need to make mentally is that unlike Class components, Function components are run on every single render. And since they are just simple functions, they internally have no state of their own.

As an aside, you can optionally make useEffect call only on the initial mount and final unmount by passing in an empty array ([]) as another argument.

useEffect(() => {

console.log('mount');

return () => {

console.log('will unmount');

}

}, []);

You can read about useEffect in detail here.

React Hooks Mental Model

So when you are thinking about Function components with Hooks, they are very simple in that they are rerun every time. As you are looking at your code, imagine that it is run in order every single time. And since there is no local state for your functions, the values available are only what React has stored in its state.

As opposed to Class components, where specific methods in your class are called upon render. Additionally, you might have stored some state locally in a state variable. This means that as you are debugging your code, you have to keep in mind what the current value of a local state variable is.

This slight difference in local state can introduce some very subtle bugs in the Class component version that is worth understanding in detail. On the other hand thanks to JavaScript Closures, Function components have a more straightforward execution model.

Let’s look at this next.

Subtle Differences Between Class & Function Components

This section is based on a great post by Dan Abramov, title “How Are Function Components Different from Classes?” that we recommend you read. This isn’t specifically related to React Hooks. But we’ll go over the key takeaway from that post because it’ll help you make the transition from the Class components mental model to the Function components one. This is something you’ll need to do as you start using React Hooks.

Using the example from Dan’s post; let’s compare similar versions of the same component first as a Class.

class ProfilePage extends React.Component {

showMessage = () => {

alert('Followed ' + this.props.user);

};

handleClick = () => {

setTimeout(this.showMessage, 3000);

};

render() {

return <button onClick={this.handleClick}>Follow</button>;

}

}

And now as a Function component.

function ProfilePage(props) {

const showMessage = () => {

alert('Followed ' + props.user);

};

const handleClick = () => {

setTimeout(showMessage, 3000);

};

return (

<button onClick={handleClick}>Follow</button>

);

}

Take a second to understand what the component does. Imagine that instead of the setTimeout call, we are doing some sort of an API call. Both these versions are doing pretty much the same thing.

However, the Class version is buggy in a very subtle way. Dan has a demo version of this code for you to try out. Simply click the follow button, try changing the selected profile within 3 seconds and check out what is alerted.

Here is the bug in the Class version. If you click the button and this.props.user changes before 3 seconds, then the alerted message is the new user! This isn’t surprising if you’ve followed along this chapter so far. React is using the SAME instance of your Class component between re-renders. Meaning that within our code the this object refers to that same instance. So conceptually React changes the ProfilePage instance prop by doing something like this:

// Create an instance

const ProfilePageInstance = new ProfilePage({ user: "First User" });

// First render

ProfilePageInstance.render();

// Button click

this.handleClick();

// Timer is started

// Update prop

ProfilePageInstance.props.user = "New User";

// Re-render

ProfilePageInstance.render();

// Timer completes

// where this <=> ProfilePageInstance

alert('Followed ' + this.props.user);

So when the alert is run, this.props.user is New User instead!

Let’s look at how the Functional version handles this.

// First render

ProfilePage({ user: "First User" });

// Button click

handleClick();

// Timer is started

// Re-render with updated props

ProfilePage({ user: "New User" });

// Timer completes

// from the first ProfilePage() call scope

alert('Followed ' + props.user);

Here is the critical difference, the alert call here is from the scope of the first ProfilePage() call scope. This is happens thanks to JavaScript Closures. Since there is no “instance” here, your code is just a regular JavaScript function and is scoped to where it was run.

The above pattern is not specific to React Hooks, it’s just how JavaScript functions work. However, if you’ve been using Class components so far and are transitioning to using React Hooks; we strongly encourage you to really understand this pattern.

Summary

This allows us to think of our components just as regular JavaScript functions. No special order of our lifecycle methods being called and no local state to track. Here’s the key takeaway:

“React simply calls your function components over and over again when it needs to render it. You’ll need to use React Hooks to store state and plug into the React render lifecycle. And thanks to JavaScript Closures, your variables are scoped to the specific function call.”

We hope this chapter helps you create a better mental model for understanding Function components with React Hooks. Leave us a comment in the discussion thread below if you want us to expand on something further.

For help and discussion

Comments on this chapter